Deepfakes have been ranked as the most dangerous AI threat, but new research suggests the pen is mightier than the picture.

Scientists at the MIT Media Lab showed almost 6,000 people 16 authentic political speeches and 16 that were doctored by AI. The soundbites were presented in permutations of text, video, and audio, such as video with subtitles or only text.

The participants were told that half of the content was fake, and asked which snippets they believed were fabricated.

When shown text alone, the respondents were only barely better at identifying falsehoods (57% accuracy) than random guessing.

They were a bit more accurate when given video with subtitles (66%), and far more successful when shown both video and audio (82%).

The study authors said the participants relied more on how something was said than the speech content itself:

The finding that fabricated videos of political speeches are easier to discern than fabricated text transcripts highlights the need to re-introduce and explain the oft-forgotten second half of the ‘seeing is believing’ adage.

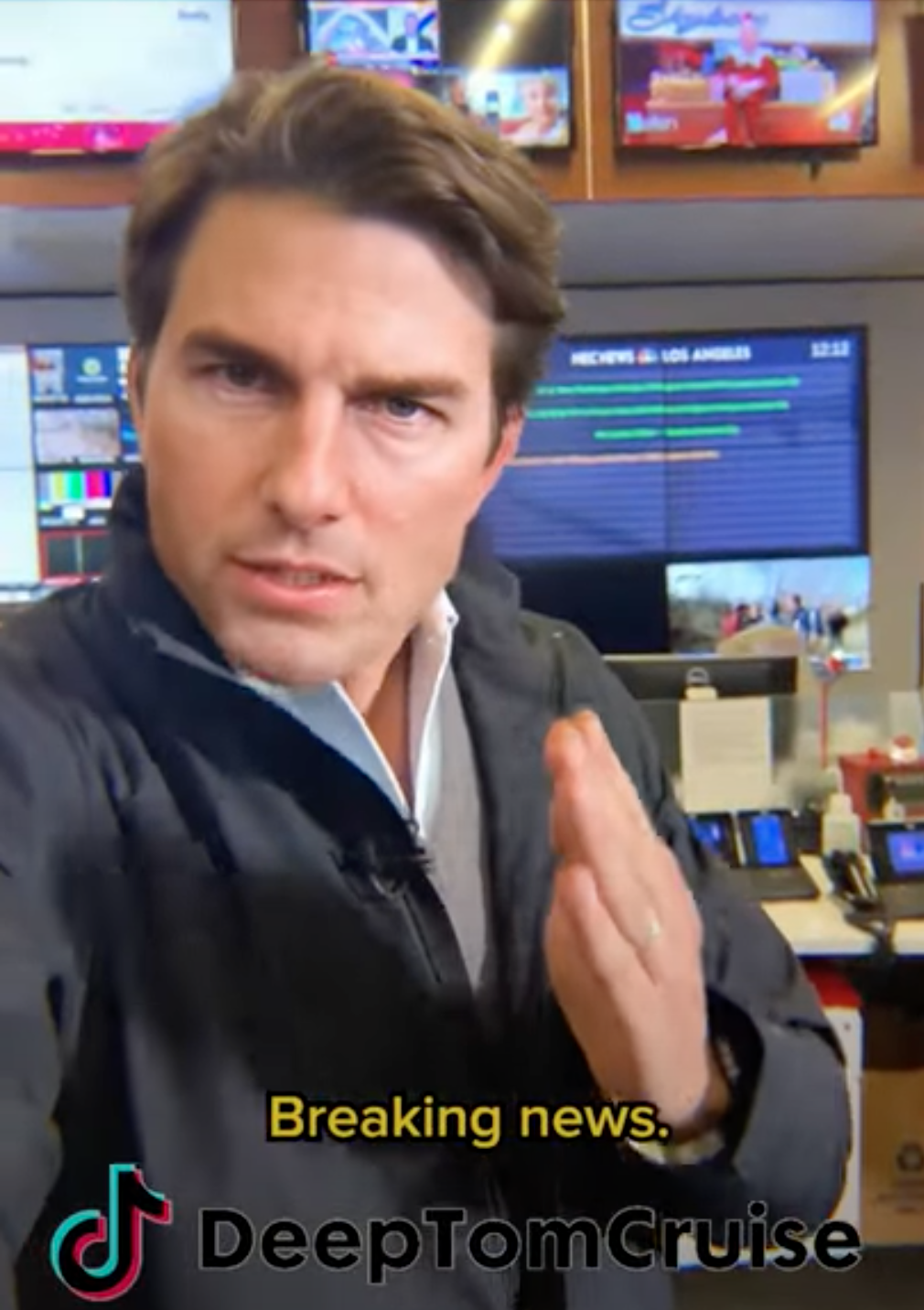

There is, however, a caveat to their conclusions: their deepfakes weren’t exactly hyper-realistic.

“The danger of fabricated videos may not be the average algorithmically produced deepfake but rather a single, highly polished, and extremely convincing video,” the researchers warned in their preprint study paper.

The study comes amid fears that Russia will circulate deepfake videos of Ukraine’s president announcing a surrender.

These concerns are understandable. However, much of the misinformation currently spreading doesn’t involve deepfakes.

Some researchers are more worried about people sharing images that look like they’re from the current war — but are actually recycled from older events.

“It’s a lot easier for someone to search around for a photo or video and repost it rather than create a deepfake, which are hard to make,” Daniel Funke, a reporter on USA Today’s fact-checking team, told Axios.

Similar observations were made in the run-up to the 2020 US presidential election.

While researchers warned that deepfakes could influence the results, outright lies and basic editing were far more prominent forms of spreading misinformation.

This doesn’t mean that deepfakes are not a danger. But more primitive deception techniques may currently pose the greater threat.

This story is adapted from the Neural newsletter. You can subscribe to it right here

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.